Deconstructing The Colonial Gaze; The Power of The Photograph in Ethnography

how irresponsible pictures can misrepresent indigenous communities

Anthropological movements like Franz Boas’ cultural relativism are sidelined today as no-brainers. As a society, we are convinced that we have matured beyond the petty antics of our predecessors, ascended above the “othering” of foreign cultures. The colonizer is dead, we tell ourselves, and with it, the colonial gaze scrutinizing indigenous peoples has also subsided. We no longer create daguerreotypes of enslaved people to show polygenesis, or sell carefully positioned images of Native tribes as spectacles.

Yet, photos like “Afghan Girl” still exist, where the central figure, Sharbat Gula of Nasir Bagh refugee camp was commodified and sold extensive copies yet never received a single penny in royalties by National Geographic or photographer Steve McCurry.

The colonizer may be dead, but the colonial gaze lives,

And this gaze is not only limited to professional photographers, but extends towards common individuals snapping pictures from their phones.

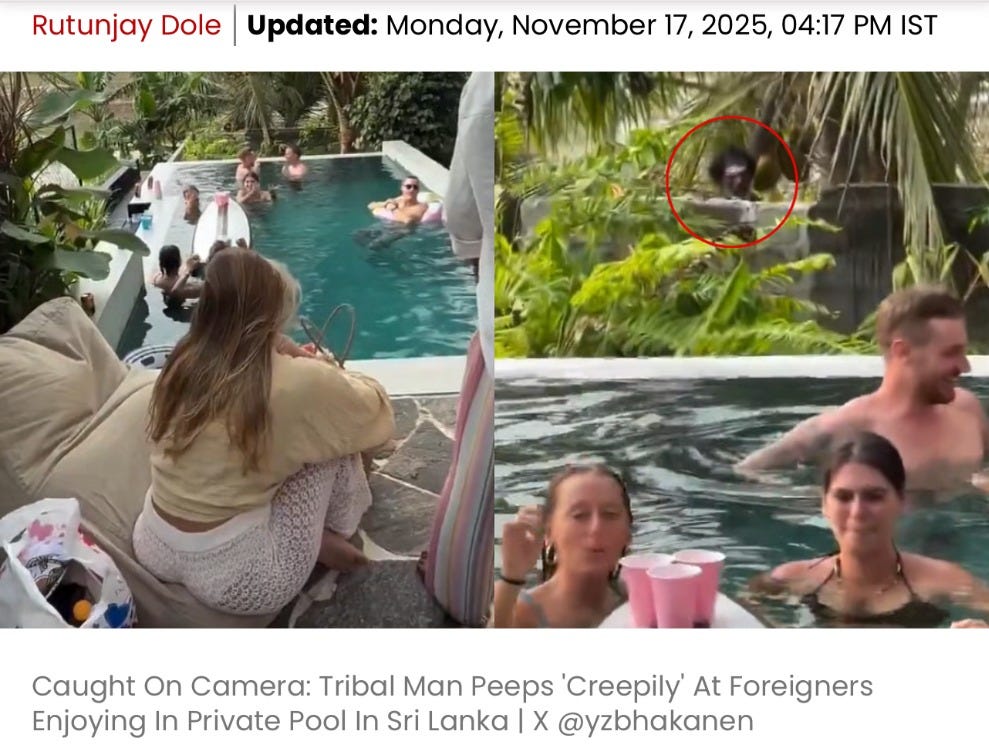

On Instagram, I watch a clip of white tourists in a sky-pool amidst the forests of Sri-Lanka. One of the tourists records an indigenous man standing in the thicket behind the pool, the tourists zooms in and lets the camera linger on the man’s solemn expression, his coiled hair, and the mark of white paint over his forehead.

I think of Susan Sontag and her befitting argument that photography is an act of ownership. “To photograph,” says Sontag, “is to appropriate.”

By recording the local, the tourist makes a selection about his portrayal, he decides how this man will be known to to the internet, as a nameless intruder, absurd and estranged in his own land. The tourist claims ownership of the man and his state in that singular moment. By pressing post, he makes that temporary segment of time a permanent reality, even a repeated one. By pressing play, I become complicit in witnessing the digital entrapment of a human being, chained to a constructed narrative, appropriated and abused by people who do not understand him, people who do not even know his name and are for lack of better words, left to refer to him as “indigenous man.”

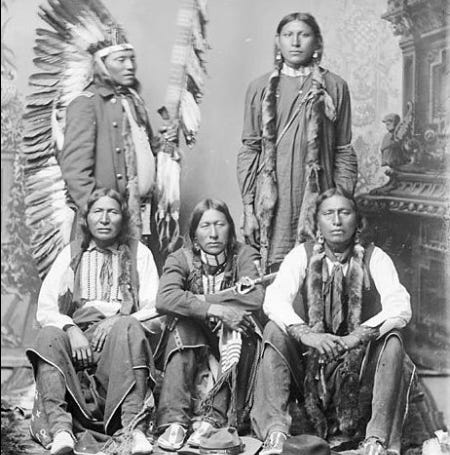

If we have invented the cruel machines that allow this, we may also invent a way to salvage the past and crawl back into it. If this happens, we must apologize to The Lakota, we must apologize that they were called superstitious when they said a photograph could take your soul away.

Many Native American tribes were forced to pose for photographs, many allowed photography, and others, like some Lakota resisted photographs.

A photograph can take away the fact that you may have been born with your eyes wide open watching the world in disbelief, or that you were born with your eyes pressed shut like a tulip. It could take away the story of how your mother held you in the dark or how you first learned to say please. It could take away the memory of your firstborn who died hungry, or how your father’s grave was unearthed by a foreign company.

It is in a time like this, where we photograph people everyday with no account for the brutality of our own perspectives, that I realize the importance of ethnographic filmography like Dennis O’Rourke’s Cannibal Tours.

Cannibal Tours is an instance where a camera is not used against the indigenous as a weapon but instead as a tool to allow contact and communication. When O’Rourke records the tribespeople of Papua New Guinea, they are given agency over their portrayal; they have the power to chose what they want to say to the world and how they want to look at the foreigners watching them on their screens.

Clip from Cannibal Tours by Dennis O’Rourke (1988) from Archivo Anthropología Visual (2016)

Though, ultimately, the decision of whether or not what they say makes the final cut falls on O’Rourke and his team alone.

It is an inevitable truth that photography and videography will always be a process of selecting and omitting. Our short lives limit the time we can lend to the story of another. We can not share the totality of experience, we can not always know what a stranger’s mother called them, but that does not mean they must remain a stranger altogether. We can know something, if not everything.

Thus, to photograph becomes a choice, a selection of what must be communicated, what must be conveyed. If you can only know one thing about this stranger halfway across the world, what should it be? The people who make this choice are the people who have control over the narrative. Their role must be seen as inexhaustibly important, not because of an arrogance about their civilization, but because of an acute awareness of the immense responsibility they carry.

O’Rourke claims ownership over the self-directed portrayals of the tribespeople and uses them to tell a story. We do not know if this is the story the tribespeople want to tell, we only know that the parts of themselves they let O’Rourke and his camera lens borrow are the parts they wanted to share with the world.

With this knowledge, the viewer has a responsibility to understand a narrative communicated through film first like a deconstructed cheesecake; understanding the taste of each component in isolation, seeing the interviews of the Papua New Guinea tribesmen as individual stories, filmed in separate segments of time, acknowledging that each interviewee was not seeking to be part of a bigger picture, but instead participating in a sort of conversation with the viewer, responding to questions unheard by the latter. These are flakes from dreams that we turn into sources, from them, we extrapolate and interpret, we create an extremely subjective reality. That is, not to say that it has no worth or viridity, but that it’s status as “subjective” must always be acknowledged.

Secondly, the viewer can then see the film as how O’Rourke has intended, a sum of parts, a whole, a complete story. But this is O’Rourke’s story, this is O’Rourke’s understanding of how other people understand things. It is nonetheless important to tell stories like that, stories of one’s own understanding.

They only become harmful when they view what is being photographed or filmed as the object rather than the subject. This thin distinction is what determines whether we impose our predisposed views over a stranger, the way the tourist records the tribal man without his permission, without having communicated with him, only as a form of ridicule, or whether we are able to contact and understand a people by allowing them to offer aspects of themselves to us which we can interpret to create ideas.

Calling The Shots,: Aboriginal Photographies, compiled by Jane Lydon, revisits an archive of photographed indigenous communities and shows that an image is not limited to being a violation against the subject, but can be used as a way to speak across distance, both in culture and time. It shows, for instance, that that the Ngarrindjeri people “embraced photography as a means to record their history, and represent their world-views.” (Hughes and Trevorrow’s, Calling The Shots, 2014)

In this way, we come to see the photograph which is controlled by the subject as a powerful act of preservation; an evidence for the existence of a culture, and as a way to interact and share oneself with others.

In an era of rapid digital media, we take photographic agency for granted. We are often ignorant of the power of a photograph to control the narrative, and the importance of the subject’s consent and participation in the construction of their own portrayal.

In a time like this, ethnography and social anthropology is incredibly relevant. It emphasizes on the need for a conscious photographer and an informed subject in working together to create an intentional piece that communicates across time, memory, and culture.

The study of ethnographic anthropology teaches us that it is not photography itself that we should be afraid of, but rather an irresponsible photographer.

I'm enjoying your recent think pieces, hope you keep it going. You have a unique mind